The Heraldry of the Whitney Family

HERALDRY IN GENERAL

Before considering the various heraldic achievements of the Whitneys I thought it might be interesting to have a review of the fascinating history and meanings of the various items that constitute what we all refer to as "coats-of-arms".

The custom of bearing devices on military shields began long ago among ancient peoples as wide apart as the Chinese and Japanese, the Assyrians and the Hittites, the Egyptians, the Greeks and the Romans but the symbols were mainly of historical heroes or of mythical derivation. It was not until the 11th C. that Heraldry , as it came to be known, commenced in Europe and the 12th C. in England and it started with the practice of wearing a surcoat over the suit of armour, bearing a pattern or symbol personal to the wearer, thus enabling him to be recognised even when his face was obscured by a closed helmet.

The decorations soon spread to shields, horse-trappings and banners and so much did the custom proliferate that, in order to reduce confusion, the King (Henry V, 1413-1422) forbad the assumption of armorial bearings without his permission. Subsequently King's Heralds toured the country, registering not only "arms" but also the births, deaths and marriages of armorial families to secure that arms were properly handed down. Many of their Rolls of Arms are preserved in the College of Arms in London which was established in the 15th century and they are a valuable source of authenticity but sometimes even so-called "bogus arms" (i.e. where they were assumed without sanction) were handed down and became recognised through usage. Arms are still granted by the College but only after stringent examination of the worthiness of the applicant and a payment which could be as much as £2,925! No one is permitted to claim an established coat-of-arms unless direct descendancy from the original owner can be proved, but there is no restriction on the display of arms as long as it is for purely artistic purposes.

The correct term for a full coat-of arms is an achievement. It usually consists of four parts the shield, the helmet, the wreath, and the mantling. There may also be a crest, supporters on each side of the shield and a motto.

The recorded description of an achievement is known as a blazon and it is written, in an abbreviated form, in Heraldry's own special language which is mainly Norman French with a smattering of Latin, Anglo-Saxon, Old English and other sources. (Reference to Heraldic Dictionaries is, therefore, essential.)

Their are many beautifully illustrated books on Heraldry (which includes, in addition to coats-of-arms, other allied subjects such as seals and banners) but to obtain details of blazons we have to go to the very expensive The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales, by Sir Bernard Burke, C.B., LL.D., Ulster King of Arms, first published in 1842. This has 1153 pages of blazons, each page having about 55 entries so that, in all, there are some 60,000 coats for about 3,500 families. There are also 74 pages on Heraldry matters in general and 23 pages of mottoes, but unfortunately, no illustrations' of individual coats. The only other book which attempts to cover all the records ( and also is without illustrations) is Papworth's Ordinary of British Armorials, by John Woody Papworth, published in 1874. This book is also of a monumental size but in this case blazons are listed first by description and then attributed to their holders, i.e. the opposite method to that of the General Armory,

and as, for example, there are at least 40 different ways of portraying a lion, 50 different styles of crosses and even a single line can be varied in 22 different ways, it follows that it is far from easy to track down any particular coat-of-arms!

If we add to the foregoing the fact that there are many rules (some of which were inevitably broken on occasion!) as, for example, how colours shall be used or decorations shall be added to the shield, it will be seen that the re-creation of any particular coat cannot be undertaken without considerable study of the whole subject. However, to return to the blazon, first the shield (and supporters, if any) are described. Any divisions are described and the colours stated, as are any decorations ("charges") placed on it. Its shape is not mentioned and as this varied considerably over the centuries, it is usual for the depicting artist to choose the one best suited. Then the crest is described, but these were not in use until the end of the 14th C. and some families never adopted one. In its absence it is usual to display ornamental plumes of feathers. Occasionally there follows the motto the family have adopted and exceptionally the date of the original grant is given. The remainder of the achievement is left to the artist to depict in acceptable heraldic fashion.

The blazon is enhanced by the addition of a helmet, wreath and mantling. There are rules concerning the type of "helm" depicted and the direction in which it faces because it is an indication of rank.

The wreath (or "torse") is a twist of two or three pieces of fabric, and usually each takes one of the principal colours of the shield. It first appeared in the 14th C. and may have developed from a scarf or even the custom of wearing a lady's "favour" around the top of the helmet. In relevant cases the wreath is replaced by a medieval hat termed a "chapeau" (or "cap of maintenance") or, in the higher ranks, by a crown or crest coronet.

The crest, which surmounts the wreath, is always depicted to the best advantage, irrespective of which way the helmet is facing, which means that it usually faces left, even if the helmet faces the viewer. Some crests are extremely fanciful and purely artistic but others may well have actually existed, perhaps having been made from leather which had been boiled and then moulded when pliant ("cuir bouillée").

Mantling is the name given to the ornamental drapery dropping from the top of the helm and it is supposed that this originated in a small cape to provide some protection from the heat of the sun. Up to the 14th C. the colour was usually red with a white or silver lining, but then it became customary to use one of the colours of the shield with either a silver or gold lining. Artistically it embodied stylised tatters, developed and enlarged until sometimes it came right down both sides of the shield and could even end in large tassels.

The motto may be depicted on a scroll, either above or below the achievement. Not every family adopted one and successive generations could always change it if they so desired. They were often in Latin or French but by no means always.

One further term needs mention. Where a shield is divided into four, understandingly it is referred to as being "quartered". However, where shields also include other arms brought in by, for example, by marriage the whole is still said to be a Quartering, no matter how many there are.

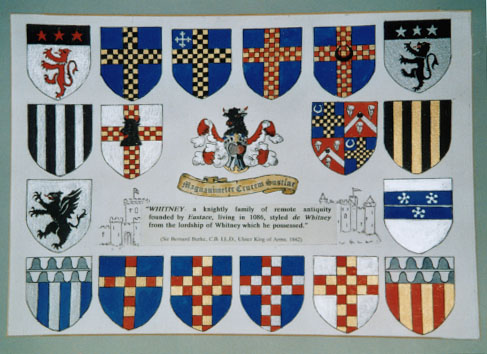

THE PICTURE OF 18 SHIELDS

Starting at the left-hand corner and going from left to right the only information I have been able to find is as follows (NOD indicating "No other details"):-

(1) Whitney, Ireland. (2) Whitney, Herefordshire. (3) Sir Benjamin Whitney, born 1833, Clerk of the Crown, Co. Mayo, only son of Nicholas Whitney of Old Ross, Co. Wexford. (4) Sir Robert Whitney, 1634. (5) Eustace Whitney, 1634 (black crescent denotes eldest son). (6) Whitney, NOD.

(7) Whitney (or Witnee), Gloucestershire. (8) Pauline Payne Whitney, 1918. (9) Fetherston-Whitney. Name changed from Fetherston, 1859. Fetherston arms in second and third quarters. (10) Witney, or Wetney, Gloucester.

(11) Whitney, NOD. (12) Whitney, or Witney, NOD.

(13) Whitney, NOD. (14) Whitney, NOD. (15) Eustace and Robert de Whitneye or Witeneye, 14th C. (16) Eustace and Robert de Whitneye or Witney, 13th C. (17) Sir Eustace Whitney (18) Witney, Chester.

The depiction in the centre shows a helmet, facing the viewer with the visor open, denoting the rank of Knight and surmounted by a Wreath and the Whitney Crest.

THE ACHIEVEMENT OF SIR EUSTACE DE WHITNEY, 1285

This is my own artistic depiction, based on the blazon of "Azure, a Cross counter-companee Or and Gules" as stated on the St. George Roll of 1285

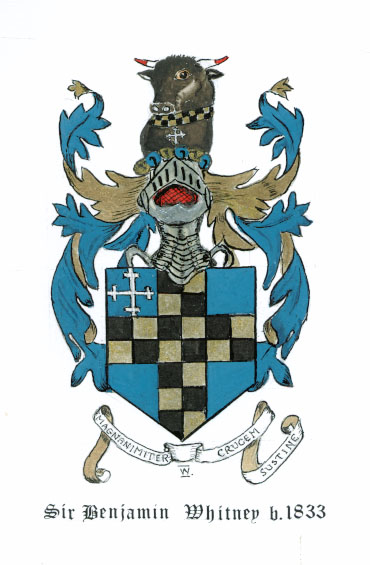

THE ACHIEVEMENT OF SIR BENJAMIN WHITNEY

My painting, copied from original

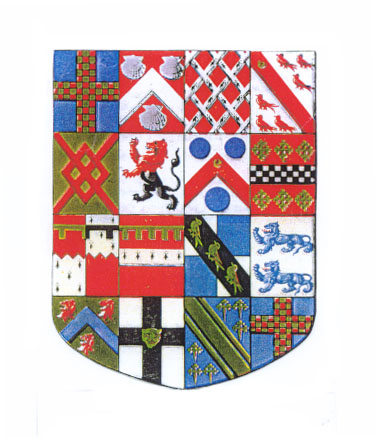

GUISCARD'S QUARTERINGS

(Origins unknown)

THE PANEL OF EIGHT

(1)Whitney. (2) Pychard. (3) Clamvow. (4) Russell.

(5) Parrey. (6) Wye. (7)Vaughan. (8) Lucy.

THE PANEL OF FIFTEEN

(1) Whitney. (2) Milborn. (3) Eynesworth. (4) Furnival. (5)Audley.

(6) Lovelock. (7) Baskerville. (8) Montgomery. (9) Rees. (10) Wallia.

(11) Le Grosse. (12) Bedmarden. (13) Solers. (14) Shandos. (15) Blackett.

HARLEIAN MANUSCRIPT QUARTERINGS

WHITNEY QUARTERINGS

As tricked upon Harleian Manuscript No. 1545, fol. 69,

In the British Museum.

(1) Whitney. (2) Milbourn. (3) Eynesworth. (4) Furnival.

(5) Verdon. (6) Lovelock. (7) Baskerville. (6) Botoler.

(7) Rhys. (8) Lenthal. (9) Grosse. (10) Bedmarden.

(11) Solers. (12) Bruges. (13) Blackett. (14) Whitney.

THE IMPALED ACHIEVEMENT

of Sir Robert Whitney and his wife Dame Sybil Baskerville.

Marshalled by C.E. Gildersome-Dickinson of London.

This shield is divided down the centre. The lefthand side reads:-

(1) Whitney of Whitney. (2) Milbourne of Tillington. (3) Eynesford of Tillington. (4) Furnival of Munden Furnival.

(5) Luvetot of Worksop. (6) Ledet of Hamerick. (7) Folliot of Hamerick. (8) Reincourt of Hamerick.

(9) Morville of Isell. (10) Engayne. (11) Trivers. (12) Stuteville of Kirk Oswald.

(13) Baskerville of Icomb. (14) Rees of Wales. (15) Lenthal. (16) Le Gros.

(17) Botler. (18) Pedwardine. (19) Solers. (20) Pavely.

(21) Bruges of Letton. (22) Pychard. (23) Sapie. (24) Delamere.

(25) Blacket of Icomb. (26) Whitney of Whitney. (It is a puzzle why this cross has four lines of chequers. All other representations and sources state three.)

The righthand side reads:-

(1) Baskerville of Eardisley. (2) Rees of Wales. (3) Lenthall. (4) Le Gros.

(5) Botler. (6) Pedwardine. (7) Solers. (8) Paveley.

(9) Bruges of Letton. (10) Pycard. (11) Sapie. (12) Delamere.

(13) Breynton of Stretton Sugwas. (14) Milbourne of Tillington. (15) Eynesford of Tillington. (16) Furnival of Munden Furnival.

(17) Luvetot of Worksop. (18) Ledet of Ramerick. (19) Folliot of Ramerick. (20) Reincurt of Ramerick.

(21) Morville of Isell. (22) Engayne. (23) Trivers. (24) Stutville of Kirk Oswald.

(25) Baskerville of Icomb. (26) Rees of Wales. (27) Lenthall. (28) Le Gros.

(29) Botlar. (30) Pedwardine. (31) Solers. (32) Paveley.

(33) Bruges of Letton. (34) Pycard. (35) Sapie. (36) Delamere.

(37) Blacket of Icomb. (38) Baskerville of Eardisley.

[Editorial comment by Robert L. Ward] The reason for the duplications is that she was his first cousin once removed, and shared descent from many of the same families. The relationship was like this:

Simon Milbourne = Jane Baskerville of Icomb

___________|_______________________

| |

| John Breynton = Sybil Milbourne

James Whitney = Blanche Milbourne |

| |

| Sir James Baskerville = Elizabeth Breynton

| _________|

| |

Sir Robert Whitney = Sybil Baskerville of Eardisley

The two Milbourne daughters were coheiresses of their parents, so both were entitled to quarter all the arms their parents were entitled to bear. Elizabeth Breynton was an heiress, too, so all the arms of John Breynton appear in her achievement, and thus were passed to her daughter Sybil, along with those of Sir James Baskerville. To add to the confusion, Sir James Baskerville's great-grandfather was a brother of the above Jane Baskerville's father (and she, too, was an heiress), making this family even more inbred, and adding to the quarterings. [End of comment]

TAILPIECE

In the portrayal of the Whitney arms in Phoenix's (see right) book the artist has omitted the helmet and mantling. This was usual in very early heraldry but what is unusual is that the shape of the shield shown was not used in heraldry until the period 1750 to 1850.

Email comments or queries would be welcome. Go to Bill Whitney's User page, look at the "toolbox", and click on "E-mail this user".

See also Some Feudal Coats of Arms from Heraldic Rolls 1298-1418.